The Law of Social Proof: Everybody's Doing It

How to be your own person in the age of social media

Social proof can lead you places you really don't want to go

Social proof can lead you places you really don't want to goI was browsing through the news yesterday, happily convinced of the rationality of humankind (well, sort of), when I came across an item concerning a so-called "mystery illness" in a school in England.

Actually, it was referring to something that happened a while ago (Hayes, n.d.), but I recall hearing about it at the time as well.

Back in 2004 a total of 53 pupils and adults were taken to hospital after suddenly developing sickness and headaches at Collenswood School in Stevenage.

This was alarming to say the least.

Strangely, though, doctors could find nothing wrong with any of them.

Consultant clinical psychologist Khwaja Abbas said, "When one person feels ill it is not uncommon for others around them to have the same symptoms. It is not hypochondria; the symptoms can be quite real. Mass hysteria is a likely explanation for what happened at the school."

Mass hysteria?

Really?

Of course, you and I would be immune to this kind of psychosomatic spread of disease, right? Maybe. But maybe not, because of course when you are in the middle of it you don't know what's going on. And if you're in the river when there's a torrent, it's easy to get swept along.

So how do we catch a 'thought disease'?

And, more crucially, how can we stay out of that raging torrent?

The dangers of blindly following the herd

Actually, the fact that people can develop these 'symptoms' of mass hysterias tells us something strangely encouraging about people.

First off, it proves that we pay one another attention, even if it doesn't always seem that way. Second, it is evidence that we are all 'social beings' with a primal need to be connected to others.

But the flip side of our connectivity is that we are all vulnerable to what Robert B. Cialdini (1984) has termed 'social proof'. We are highly susceptible to being influenced by 'the herd'.

And sometimes the herd might lead us off a cliff.

Stand back and smell the tulips (but maybe don't buy one!)

Musing over the concept of social proof, I remembered the tulip 'craze'.

The story begins in 1559. Conrad Guestner brought the first tulip bulbs from Constantinople to Holland and Germany, and people fell in love with them. Soon tulip bulbs became a status symbol for the wealthy because they were beautiful and hard to get.

Early buyers loved tulips. And as the tulip craze spread and their popularity boomed, tulips started to be bought and sold as stock commodities. It certainly seemed as though buying tulips was a good investment.

Why?

Well, everyone was doing it!

Eventually (but quicker than you might imagine; social-proof behavior can spread like wildfire) the most expensive bulbs sold for up to $76,000! Can you imagine spending $76,000 for a single tulip bulb? Maybe not.

But what if everyone around you accepted this as normal behavior?

From getting tattoos to throwing cash at cryptocurrency to trying the latest diet, so often we do things purely because others do it. It must be good because, well, just look at the herd!

Of course, sometimes it is a good idea to follow your herd instinct. Sometimes lots of people do something for good reason. We can all feel grateful that hygiene took off. It wasn't always standard practice, even in medicine.

We are more likely to stop smoking if our spouse, friends, and co-workers stop, and this effect holds true even when it's friends of our friends that stop smoking (see Christakis & Fowler, 2008). But the same holds true of divorce, obesity, and unhealthy exercise habits. How likely we are to do any of these things is heavily dependent on whether those around us do or don't do them.1

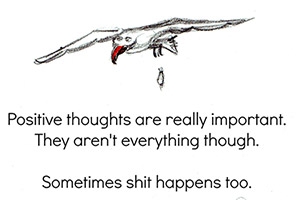

Of course, sometimes it can turn out that 'everyone' was wrong.

When social proof goes wrong

Back to the tulip mania. Eventually the bottom fell out of the market and people had to sell, sell, sell. Europe was left wondering what all that fuss about tulips had been about! Tulip prices soon plunged to less than the present equivalent of one dollar each. Those who had bought a tulip bulb for $76,000 found that a mere six weeks later it was worth less than a dollar.

You may already be drawing similarities between this and the dot-com boom and bust around the turn of the century. Again, against normally-savvy investors' better judgement, billions of dollars were sunk into companies that, in hindsight, had no solid business model. But of course, everyone was doing it - and no-one likes to miss out on an opportunity!

From bystander apathy to spreading low morale, it's easy to get swept up with what others are doing. But sometimes we need to decide what is right for us.

Anything can come to seem okay if everyone else seems to be doing it. And I do mean anything.

How could I have done that?

The more people engage in a particular behavior, the more acceptable this behavior becomes. No matter what the behavior.

If a female friend of yours went around wearing mouse skin over her natural eyebrows you might think she was... unusual. Yet back in the late 18th century this was a common trend.

From to body piercing and the wearing of horrendously flared trousers in the 1970s (guilty!) to medieval witch hunts and Nazi Germany, sometimes we may convince ourselves we are expressing our individuality when we are in fact doing the reverse.

Usually the individual will feel that they have acted because of a logical chain of reasoning. They've come to their own decision. At least that's the way it feels.

But just how far does the law of social proof actually affect what we do?

Denying the evidence before your own eyes!

In one experiment (Asch, 1956), five primed students were told to describe a circular shape as being "like a square".2 A sixth (unprimed) student, on hearing the others describe the clearly circular object as being like a square, was 81% more likely to also say the round object was square. If the other five students said it was circle-like then the sixth student would describe it as being circular. What does this tell us about the psychology of jury service?

And how about the research cited in Robert Cialdini's (1984) famous book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion?

After the death of a famous person, the suicide rate increases dramatically in areas where that death has been highly publicized. Vulnerable people, it seems, decide what to do on the basis of what a celebrity has done (Cialdini, 1984:146)!

We frequently assume that the teenage years are a time of rebellion. However, it is usually only parents who are rebelled against. Teenagers are among the biggest social conformers: they dress, walk, and talk in similar ways to their friends. A truly individualistic, rebellious teenager would not let their actions be dictated by social proof!

Social proof can sometimes work for us. If lots of people are eating healthily, by all means we should jump on the bandwagon. But we need to know the limitations of social proof. Use it but not be abused by it. And also learn to recognize when it might be working on us.

Knowing how to work around social conformity might even save your life.

What to do if you are mugged

Consider the well-known phenomenon of bystander apathy. People have been robbed, raped, and even murdered in crowded areas while good people looked on but failed to help. Why? Because of the diffusion of responsibility. If no one else is helping, maybe the right thing to do is not to help. Or perhaps someone else is helping. Surely someone else has called the police!

If (heaven forbid!) you are ever attacked in a crowded place, don't just shout for help. Rather, focus your attention on one individual, look them in the eye and say, "You with the blue shirt, help me!" You are much more likely to elicit a response because you are appealing to an individual, not a crowd, making it much harder for the individual to defer responsibility.

Mind you, sometimes we can feeled mugged by marketers!

It must be good; everyone's buying it!

Advertisers use social proof as a matter of course these days, claiming their product is the 'fastest growing' or 'largest selling', that 'a million Americans can't be wrong' or that an 'international bestseller' has sold millions of copies!

And again I'd like to emphasise that before we dismiss social proof out of hand and always try to go against herd instinct, we need to be fair. Much popular behavior is valuable, as I've said, and the fact that many people do it may be a good sign that we should follow suit. Regular dental checkups, exercise, and financial advisement, for example, are activities engaged in by millions with good reason.

It's only when we blindly follow the masses that our individual integrity is threatened - especially when that quiet voice says, however briefly, "Is this really right?" before being drowned out by the roar of the crowd. But if we go against the herd at any opportunity then our behavior is no less mechanical than the social-proof-induced actions of a Nazi or a fashion victim.

So with this sort of pressure, how can we be ourselves and steer our own ships? How can we truly be individuals?

On being an individual

Many of us feel we ourselves are above the influence of social proof. We use rationalizations to justify why we do or say things rather than admit to ourselves that we are really just following the crowd. But it's important to know one thing.

There are always people who remain themselves even as behaviors and attitudes sweep through social networks. You don't have to believe things simply because other people believe them. You can, and, if you want to really be you rather than a replica of everyone else, must discover what you think. What you feel is right.

We need to be influenced by those around us for society to function, but we also need to understand that more people doing something or, as in the case of mass hysteria, feeling something doesn't necessarily make it right.

Recall the story of The Emperor's New Clothes. Although the king was naked, none of his thousands of subjects would admit (even to themselves?) that he wasn't wearing fine new clothes (the cunning tailor had said that only a fool wouldn't be able to see the fineries).

It took the direct perception and straightforwardness of a child in the crowd to point out the Emperor was, in fact, stark naked.

We all need to find that childlike perception sometimes.

References

- Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70(9), 1-70.

- Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2008). The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(21), 2249-2258.

- Cialdini, R. B. (1984). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Quill.

- Hayes, D. (n.d.). School illness was 'mass hysteria'. Evening Standard.

Endnotes

- Check out this TED Talk online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2U-tOghblfE

- See also this Youtube clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sno1TpCLj6A