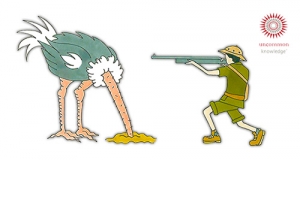

How Not to Get Radicalized

Where your beliefs come from and how to avoid being manipulated by them

Understanding how belief works can stop others lighting a fire in your mind.

Understanding how belief works can stop others lighting a fire in your mind."The moment you are born, you become a moving target for the world. You may be much more than this, but do you remember that you are a target as well?"

- Idries Shah

When does belief become delusion? What are the typical beliefs of those with depression, jealousy, low self-esteem, or supreme self-confidence? Or of those who believe in flying-saucer cults or the Loch Ness monster? Or of those following the tenets of this or that religion, or political dogma?

Hidden or unexamined beliefs and assumptions 'lie' (often in more than one sense of the word) at the heart of many of these ways of being.

When you understand how beliefs work, you become less of an easy target.

Delusions and assumptions

I've met all kinds of people who've believed all kinds of things. Some were genuinely deluded - a couple of men who believed they were Jesus Christ, a guy who believed he was the Queen of England's brother, and a woman who claimed her face had been replaced with that of a stranger. These beliefs are extreme and obvious psychotic delusions.

But many of our own beliefs ride atop unconscious assumptions we've formed, and some of them can be almost as skewed and troublesome as true delusions.

Some beliefs hurt us. Some help us.

But one thing is for sure.

Smart people can believe dumb things

Have you ever felt baffled by how someone you thought was sensible could believe some of the things they do?

We assume that beliefs have more to do with logical, intelligent rationality than they actually do. But beliefs, especially strong ones, tend to be inculcated through emotion, not reason and logic.

Signs that a belief is emotionally driven rather than empirically arrived at include:

- The believer will become emotional whenever the belief is challenged or even discussed.

- The believer will resist and deny disconfirming feedback. They will explain away any facts or evidence that don't support their belief. They are biased towards their belief.

- The believer uses 'proof through selected instances', otherwise known as confirmation bias. For example, they might point to some men as 'proof' that all men are bad.

- The believer may simplify their ideas to all-or-nothing, black-or-white perspectives. Emotion makes us think in simplified, all-or-nothing ways, and strong beliefs often take on this all-or-nothing form.

Far from being based in logic, this kind of belief system represents an emotional reaction or conditioning. Fear or desire affects us strongly so that, rather than using our minds to check out the validity of our emotional response,we begin to rationalize and defend the emotionally conditioned 'truth'. We start to defend it in a particular way even if defending the belief isn't in our best interests.

Rationalizing and justifying

When we are induced to feel strongly about something, then unless we genuinely observe what is going on and challenge those ideas, we will start to rationalize. We then use 'logic' to back up ideas that may not be true. Logic becomes the servant of emotion.

So if you are attracted to a person (emotion), you might feel compelled to construct 'reasons' why this person is right for you even before you really know that they are. Those reasons might be right... but they might not be.

So the emotion comes first and the rationalization second.

Rationalizations begin to cement the belief in place. I feel accepted, maybe even loved (emotion), when I attend a cult meeting. Now, to keep getting those amazing, intense feelings, I may need to rationalize why flying saucers really are going to rescue us cult members while the rest of the world is left to drown.1 I start seeing 'evidence' and using it to formulate 'logical' reasons why this is bound to happen.

These rationalizations can become harder and harder to loosen or challenge, because now the brain is protecting the belief with emotion and logic.

We only look at evidence that seems to back up the belief - confirmation bias - and we begin to see reality through the lens of the belief system, that is, in simplified, all-or-nothing ways.2

If I'm convinced that a certain person is right for me, I will become emotional at any suggestion this person may not be perfect. I will ignore or explain away any evidence that they may not be as great as I feel they are. I will start to think about them in simplified, all-or-nothing ways: "But he is a good person!"

Once we come to hold strong emotionally conditioned beliefs, which are resistant to disconfirming feedback, we are said to have been 'radicalized'. And if we've been radicalized by someone else, we are said to have been 'brainwashed'.

The washing of brains

The Chinese term xǐnăo literally means 'to wash out brains'. In the West we adopted the term 'brainwashing' when, in the 50s, British psychologist William Sargant demonstrated how the Chinese succeeded in remodeling the beliefs of captive American servicemen during the Korean War.3 Some of the methods of this belief implanting included:

- Leveraging the need to maintain a sense of consistency. Initially, servicemen were induced to publicly state quite neutral statements about the USA and communist China for small amounts of food or other minor privileges. Then, over time, they were encouraged to say increasingly negative things about the USA and increasingly positive things about Chinese communism, but still for only trivial privileges. No one wants to think they have sold out for small rewards, so perhaps it's easier to assume "I must now believe it!" and adopt those conditioned beliefs.

- Social proof. We are social creatures and therefore will often come to believe what those around us believe. The Chinese used group pressure as part of their brainwashing system.

- The alternative use of fear then hope - a kind of 'good cop/bad cop' scenario - starts to destabilize personality. One moment the captive may have hope they will survive or be released; the next they may believe they will be executed. Sleep deprivation may be used alongside this technique, again to destabilize the person and therefore make them easier to condition.

These last methods are extreme, of course, but we can all be led to believe things through subtle coercion or emotional impacts that condition our beliefs.

For example, the experience of prolonged emotional abuse may 'brainwash' someone into believing they are 'no good', or unlovable, or stupid.

William Sargant also made another vital point around the formation of beliefs.

Cultural brainwashing

We like to feel that our beliefs are the result of obvious or self-evident truths. We might also like to feel that we believe what we do because of individual choices and careful reasoning.

But William Sargant made a point that now might seem obvious: he suggested that our beliefs largely stem from the accident of our environment. The accident of the location and time of our birth lands us in an environment already full of the beliefs of other people - ready-made dogmas just waiting for us to come into the world and pick them up.

These 'accepted ideas' are, as it were, grafted on to us without our conscious participation. But the point is, they feel like our beliefs. Social proof is powerful. And so is tradition.

As a result, whatever their personal characteristics or intelligence, a person born into medieval Japan would have a very different set of beliefs from someone born into the 'swinging 60s' in San Francisco.

So a question we might all ask ourselves sometimes is:

Do I believe what I do simply because of when and where I was born?

By taking our beliefs as reflections of unchanging, universal truths without ever questioning them, we begin to lose a sense of who we really might be if we thought for ourselves more.

Go back to the right time and place, and you'll find any number of idiots who knew that the Sun orbited the Earth, or that the world itself existed upon the back of a giant turtle, or that bad smells caused disease, or that hygiene in hospitals made no difference to the spread of infection among patients.

Actually, even good and intelligent people would have believed all these 'truths' at one time or another. But it took people who could step outside the assumptions of their cultures to see beyond the self-evident 'truths' of the accident of the time and place of their own births.

Did you, for example, really choose your religion or politics? Or did they, by dint of the people around you, choose you?

The engineering of belief

Many beliefs are fair and reasonable. I believe that if I jump off a building, gravity will pull me back to Earth at an unhealthy speed. But if you try to tell me gravity is just an idea, I won't feel the need to get emotional about this belief or even defensive about it. Believing in gravity works for me because it has worked for all people in all times and places (with a few caveats concerning out of space!).

But if I have a strong belief about, say, all conservatives or all liberals, I may become highly emotional and see them all as one thing. Emotionally conditioned beliefs lead people to overgeneralize. "All sinners will go to Hell!" That kind of thing.

A healthy mind is less prone to emotional indoctrination of limited and limiting beliefs.

Someone may be naturally intelligent, but if their emotional life is unstable they may fall prey to all kinds of weird and wonderful beliefs about themselves or others. It is their emotionality that renders them vulnerable to the absorption of damaging beliefs.

To ask, "How could someone be so stupid as to believe that?" is to miss the point. They believe it not with their rationality, but with their emotionality.

Hypnosis and beliefs

People sometimes assume that hypnosis is used to "make people believe things", and it can be. But as I hope I've shown, there are so many other methods of persuasion and everyday influence. These procedures and influencers are all around us.

In fact, when doing hypnotherapy with, say, a depressed person chock full of self-damaging beliefs, I need to calm their mind and body first, before presenting a wider, more balanced set of possibilities during a calm state of hypnosis.

So hypnosis can help people step outside of a limiting frame of belief to see it from the outside, so to speak, and see wider realities and possibilities.

This is not at all the same as forcing someone to believe something different. And it's worth considering something.

All the beliefs you currently have - beliefs about yourself, other people, and how the world works - at one time you didn't have.

How many of your beliefs really help you? And do they simply seem to be true because you look for evidence that supports them and discount or don't see evidence that might contradict them?

Beliefs can do a great job of masquerading as knowledge or even wisdom. But we can all benefit from learning to see which of our beliefs are based on knowledge and real, direct experience, and which are based on a kind of everyday emotional groupthink brainwashing.

When we learn to tell the difference, we have a better shot of reaching our potential.

To learn more about hypnosis, see our free 5-day course.

References

- This cult, known as 'the Seekers', is examined in the following classic social psychology work: Festinger, L., Riecken, H.m & Schachter, S. (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

- All-or-nothing thinking is also a risk factor for developing a strong depressive belief system;

- I recommend Sargant's book: Sargant, W. (1957). Battle for the Mind: A Physiology of Conversion and Brainwashing. Oxford, England: Doubleday & Co.